Parenting Resources | Strengthen Your Family Relationship

Provide Support

Help Me Complete Tasks and Achieve Goals

An important part of relationships is to provide support for each other in learning and growing. We do this by helping each other navigate through difficult situations, building each other’s confidence, advocating for each other, and setting boundaries for each other.

What Does It Mean to “Provide Support”?

Actions That Provide Support

Search Institute has identified five actions that provide support:

- Navigate: Guide me through hard situations and systems.

- Empower: Build my confidence to take charge of my life.

- Advocate: Stand up for me when I need it.

- Set boundaries: Put in place limits that keep me on track.

Getting Started: Ideas for Parents

Here are some ways moms, dads, and other parenting adults provide support to their kids:

- Offer information and practical help to solve a problem, or lend them something they may need.

- Show young people how to ask for help when they need it.

- Shift levels of support. Give more support when young people are struggling, and less when they are making progress. Step back as their skills and confidence build.

- When you teach your child a skill, demonstrate it by breaking it into smaller steps.

- When your children are not getting the help they need, find people who can address the issue.

Check It

Take a quick quiz to reflect on how you provide support in your family. Use the results to explore new ways to support each other.

| Parents | Do you already have a Family Quiz Code? Click here. | Click here to take the quiz and get a Family Quiz Code to share with your family (optional). |

| Youth* | Click here if your family has a Family Quiz Code. | Ask a parent to set up a Family Quiz Code. |

* The quiz is designed for youth ages 10 to 18.

ABOUT THE QUIZ

What’s the quiz for? This quiz is for your own reflection and discussion as a family. It is not a formal assessment.

How does it work? The first adult who takes a quiz is assigned a random number, which we call your Family Quiz Code. They then share that code with everyone else in the family. Each person just enters this Family Quiz Code when they start a quiz, and all your results are automatically combined so you can talk about them together.

Why do you need a Family Quiz Code? This anonymous code lets you see the results from everyone in your family combined.

Who will see the results? No one else will ever know your responses, unless you share them. The Family Quiz Code cannot be used to find or identify you or your family.

Talk About It

What’s the Right Amount of Support?

Everyone needs other people to help them. When we’re young children, we depend on parents or other caring adults to feed us, bathe us, and take care of us in every way. As we grow up, our needs for support change, but they don’t go away. Sometimes it’s a trick to find the right balance of having others support us and being responsible on our own. These questions encourage conversations about these issues.

Discussion Starters with Your Kids

- Think about a recent time you were struggling with a challenge. What are some ways family members helped you?

- Who is someone you admire who really encourages you to pursue your goals? What do they do that really matters for you?

- What do you most appreciate people doing to support you when you’re working toward a goal?

- What do other people do that builds your confidence when you’re working on important tasks or goals?

- When has someone stood up for you and helped you get what you needed? How did you feel after they helped you with that?

- How does setting limits or boundaries help us stay focused on our tasks or goals?

- When have people tried to help you or support you when you didn’t really want it? How did you deal with that? What might you do next time?

Discussion Starters with Other Parenting Adults*

- How do you balance doing things for your child vs. letting your child do things for themselves? How do you know when you do (or don’t) get that balance right?

- What are ways we as parents help each other navigate challenges, empower each other, advocate for each other, and set boundaries for each other? What kinds of mutual support from other parents do we most appreciate?

- How do you respond when you see your children being treated unfairly? Is it different if they’re being treated unfairly by their friends, other kids, teachers, other adults, or some larger system (such as police, or schools)?

- When has the need to support your kids changed—either because you needed to back off, or because they needed more support in some area? How did you adjust? How did that affect other parts of your relationship? How did it affect other relationships?

* These parenting adults may include your spouse or partner, extended family members, friends who are parents, or a parent group or class.

Try It

When I Needed You . . .

A big part of being family is helping each other out when needed. We’re more likely to grow and accomplish our goals when we know others in our family are there to support us by helping us navigate difficult situations, empowering us (rather than taking over), advocating for us, and setting boundaries that keep us on track. These activities invite your family to explore the ways you support each other. They complement the activities in Express Care, which focuses more on the emotional support you provide for each other.

Navigate: Guide me through hard situations and systems (three family activities)

Sometimes we encounter obstacles in life. Some will be easy to navigate; others will be really challenging—even impossible. Sometimes the obstacles are internal―such as when we don’t have the skills or experience we need. Other times, they may be major social barriers, such as laws, customs, or prejudices that prevent us from achieving goals based on gender, race, country of origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, or other aspect of our lives.

We’ll need help and support to keep going, work for change, or find new paths forward. These activities highlight the ways family members help each other navigate situations and systems to complete tasks, achieve goals, and bring about positive change.

1. A Guide Through Obstacles 30 min

Enjoy a game that brings to light some challenges of being guided and being a guide.

This game stimulates discussion about the challenges we’ve overcome and how we’ve guided each other in our families. (You’ll likely have some needed laughs along the way, too.)

- Get some hand towels, scarves, or other cloths to use as blindfolds. (Some people use children’s Halloween masks with the eye holes covered.) Have enough so that half of the people in your family can be blindfolded. (If you have an odd number of people, have one person observe the first round, then switch.)

If you have a family member who has a sight impairment, they may already know what it’s like to be guided by others. Invite them to be the guide this time.

- Pair up everyone in the family, mixing up adults and kids. Find a space that doesn’t have too many obstacles, clutter, or stairs. (You want to be safe.) Blindfold the oldest person in each pair.

- Then have the person without the blindfold guide the blindfolded person around the space (safely!). The blindfolded person should not be able to see. (If you want, make it more challenging by having no talking.)

- After several minutes (or when they’ve reached a chosen destination), switch roles and repeat.

- Then everyone sit together and talk about the experience:

- What were some of the things you did to make this activity work for you?

- What was it like for you to be blindfolded? What was it like to be the guide?

- What did the guide do that made it easier or harder to find your way around?

- What did the followers do that made guiding them easier or harder?

- What did each person do that made you trust them more (or less!)?

- Now give each person time to talk about these things (if they’d like to do so):

- What are obstacles—big or small—you’ve encountered in the past when someone has guided you around? What did they do? How did you feel about what they did?

- What made those experiences feel most supportive? What wasn’t as supportive?

- What is a current obstacle you’re facing? What are things members of this family can do to help you feel supported—or guided through these obstacles?

- What are some obstacles we’re facing together as a family? What can we do together to support and guide each other as we take on these challenges? Who else do we depend on to support us?

- Thank each other for ways they’ve been supportive in the past in facing and overcoming obstacles or challenges, large and small. Be specific in saying what others did that really mattered.

2. Overcoming Obstacles, Video-Game Style 45 min

Video games can teach us a lot about dealing with barriers and obstacles.

Many video games make overcoming obstacles part of the fun. In this activity your family will learn about dealing with obstacles by playing a video game together.

- Many video, online, or other electronic games involve overcoming or racing around obstacles to achieve a goal or move to a next level. Identify a game that a family member plays—and that’s appropriate for everyone in your family to play.

(If your family doesn’t play electronic games, think of a board game, sport, or other activity that involves overcoming obstacles to reach a goal. In basketball, for example, the other team is the “obstacle” between you and the basket.)

- Play the electronic game together, giving everyone a chance to try it. Veteran players can explain how it works, and newbies can try it so that everyone understands the basics.

- Turn off the game, and talk together about how the game works. What strategies did different people try? For those who’ve used it for a long time, what have they learned to do over time that really helps? What keeps you motivated and interested to keep playing?

- Now think of other goals you have as a family or individually. Brainstorm parallels between overcoming barriers in the electronic games and in the pursuit of your goals. Here are some examples, but you can come up with your own:

- You feel challenged and motivated by your early success, even when things start to get harder.

- You progress little by little, not trying to overcome the hardest barriers at first.

- You get small rewards as you make progress.

- You keep trying, and you get several chances.

- You get better at dealing with barriers and obstacles after you’ve had to deal with them a few times.

- Talk about some goals, large and small, that different family members have had. Discuss these kinds of questions:

- What motivated you to work toward the goal? What kept you motivated?

- What obstacles have gotten in the way? How have you dealt with them?

- What are ways we help each other navigate barriers we encounter as we explore future possibilities?

- Now think about a current goal or aspiration a family member has. What barriers do you see on the horizon? How can you help each other deal with those obstacles?

- Consider breaking the goal into “levels” like a video game, highlighting different challenges at each level before you achieve your goal.

3. Set Up Your Lifelines 20 min

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire inspires this conversation about the “lifelines” we use when working toward a goal.

A plot-thickening feature of ABC’s long-running TV show, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, is a series of “lifelines” to help contestants when they get stumped. The lifelines have changed over time, but they’ve included Ask the Audience, Phone a Friend; Ask an Expert; and 50:50.

This family activity uses the idea of lifelines to think about whom family members can turn to when they get “stumped” while working toward future possibilities.

- Start the activity by imagining that a family member has been selected to be on the TV show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. But this time, the prize isn’t money―it’s something the person really wants to do or to become. For example, a young person may aspire to attending a particular university or to excelling in a sport. An adult may aspire to a new job or becoming a master gardener.

- Think about the people you’d want to have as your “lifelines” if you get stumped on this quest. Include these lifelines:

- Phone a friend.

- Text a parent.

- Ask an expert

- Poll your family.

- Brainstorm the kinds of obstacles each of these lifelines would be best at helping you overcome. For example, a parent might be particularly good at thinking through possible solutions, and a friend may be really good at motivating you. Which of these lifelines would you be most likely to use? Why?

- Shift the conversation to thinking more seriously about the ways family members, friends, and others have helped you in the past when you’ve encountered obstacles to your goals. What are the things they did that really helped you?

- Have each family member identify a goal they’re working on now (large or small). Identify one way others in the family can be a “lifeline” right now to help them stay focused, motivated, and moving toward that goal.

6. BONUS: Send a note or call one of the people who has been a “lifeline” in the past. Thank them for what they did. Say, “We were doing this activity in our family, and I remembered when you ______. Thank you for being there for me. It really made a difference.”

Empower: Build my confidence to take charge of my life (four family activities)

Sometimes it’s hard to get the right level of support. On the one hand, we hear about some “helicopter parents” who protect their kids from any seeming hardship and “lawnmower parents” who clear a path of any bumps that might hinder their child’s journey to greatness. On the other hand, we see some kids struggling, and we wonder if their parent may not be invested enough (even if we don’t have any evidence).

Even though these examples focus on how parents can either take over or not offer much help at all, we can miss the balance of support in all of our relationships. How do we provide support while also boosting each other’s confidence to take charge of their own lives? These activities explore four strategies:

- Being clear about how you want to grow or change;

- Being a role model;

- Coaching; and

- Giving helpful feedback.

1. How Do You Want to Grow? 30 min

Being open about how you’re working to change or grow is the first step in getting support from other family members.

It’s hard to support and empower each other if we don’t know what goals each of us needs support to achieve. This activity invites family members to each identify one thing they would really like to improve—including something they may already be working on. Family members have the opportunity to build each other’s confidence by offering encouragement as they work toward their goals.

- Download and give each person a copy of the “Supporting Each Other in Positive Change” worksheet. Have each person complete the worksheet on their own (though you can certainly help each other think it through).

- Once everyone has picked a specific change to work on, have everyone talk about their plan with the whole family. Offer helpful feedback, where needed. (For more information on giving helpful feedback, download the feedback tipsheet.)

- Focus on #5, which is about how family members can support you. Ask people to talk about what they will commit to doing to help each other. If some people suggest things that seem to take over, talk about other ways they might offer support while also leaving the responsibility for achieving the goal with the person who wants to achieve it.

- When all family members have talked about their plans and how they will support each other, decide together when and how you’re going to check back in with each other. (You may want to talk about it again in a week, for example.)

- When you get back together, talk about how it went:

- Did people follow through with support? What did people do? What was harder to remember to do?

- How did it feel to know that people were interested in how you were doing with your goals? How did it affect your focus on those goals?

- What things were helpful? Awkward? Irritating?

- How did it affect work toward the goal? What might have made it better?

- What would you like to try moving forward?

2. Role Models Who Build Our Confidence 15 min

Sometimes we are inspired by what others achieve.

It can be easier to imagine ourselves achieving our goals or dreams when people we know or who are like us inspire us by their accomplishments. So who are people who inspire us, and what do we see in them that’s also true about our own family?

- Give each family member a blank sheet of paper and something to write with. (If you have colorful markers, use those.) Have each person draw two picture frames on the paper, then draw sketches (or stick figures) of two people they see as role models who are not in your immediate family. They can be celebrities or people you personally know.

- Next to each “portrait,” write down or draw things this person says or does that they admire or want to learn from. Try to think of three or four things for each person.

- Have each person tell the family about their picture and about the person they admire. It’s good to ask questions, but don’t argue with their choice. (Your goal is to understand what people admire about them, even if you disagree or dislike the person.)

- After people have all described the person they admire, talk about the kinds of actions and attitudes that different family members admire between all the different people. Does anything really stand out? Where are there big differences?

- Now talk together about the people in your own family. What do you say and do for each other that are similar to the things you admire in those celebrities? What’s different? Think of things that each family member does that inspires others to grow and be their best.

- Get a sheet of paper for each person in the family. Work together to draw a sketch of each person. Write down some of the things that person says or does that you admire and that inspire others to learn and grow. Give the picture to each person to keep as a reminder of the ways they’re role models who inspire each other.

3. How We Coach Each Other 30 min

Family members teach each other something they know as a way of exploring differences between coaching and taking over.

Each of us knows how to do something fun that others in our family don’t know how to do. It may be standing on your head, folding a napkin in creative ways, whistling, greeting others in another language, getting a smartphone to do something unusual, or nailing a particular dance step. This activity gives you a chance to coach others in how they can do this too—which means you can’t do it for them.

- Have family members each think of something they know how to do that others don’t know, but you’d like to teach them. (At least for this activity, focus on things that don’t take more than a few minutes to learn—though you could decide to teach each other more complex skills later, if people are interested in that.)

- Once everyone has picked something to teach the others, set some ground rules:

- Each person can tell others how they do it, and they can talk people through what they’re learning.

- But they can’t help them do it. The learners have to do it on their own. (You might even have people keep their hands behind their back when they are coaching.)

- Others in the family can’t coach the coach!

- Give each person time to coach the others in learning what they know. Focus on having fun together; there’s no need to get uptight if something isn’t working well.

- When everyone has had a chance to coach the others, talk about what you did together:

- What was hard or frustrating about the process? What was fun?

- What are things people did that really helped you learn? Be specific.

- What was hard about either coaching or trying to learn? Make a list of things people did that seemed to help most with your learning and staying motivated.

- What do the ways we interacted during this activity show us about how we do or don’t guide each other in our family? Are there some pitfalls or traps we fall into that we need to work on avoiding?

- What might we try differently in the next week or so to guide each other in growing, learning, and working on goals?

In the days that follow, remember what you discovered in this activity when you have opportunities to guide each other in accomplishing tasks or achieving goals.

4. Motivating Feedback 15 min

Learn about the ways we provide feedback that either fuel or freeze our motivation.

A big part of guiding growth is providing feedback that motivates each other to move forward, rather than shutting them down. A great deal of research (particularly in business1 and education2,3) focuses on effective feedback. Giving feedback as people try things is often more effective at helping people grow and learn than just telling or teaching people what to do.

This activity encourages you to think about how you give feedback to each other in your family.

- Begin by clarifying what you mean by feedback. One definition of feedback is information we give or get from each other about how we’re doing in our efforts to accomplish, learn, or get better at something. Some people think feedback includes things like advice, praise, criticism, or an evaluation. What does feedback mean to you?

- Recall times different family members have gotten feedback that helped them in important ways. It could be feedback at home, at school, at work, on a team, or in other places. Maybe it helped them learn something better, or it encouraged them to try something they hadn’t thought to try. What made that feedback valuable and motivating? Give each person time to give an example, if they have one.

- Then recall times when you’ve gotten feedback that made it hard to keep going or learn—feedback that deflated you or made you give up. What was it about the situation or feedback that made it hard to move forward? Give each person a chance to give an example, if they have one.

- Print out this tip sheet: Four Steps for Giving Motivating Feedback. Think about the examples you just discussed. Which of these things did you experience? What was missing in your experiences? Were there some things that happened in your experiences that you would add to or change on the tip sheet? (Write your changes on the sheet to make it your own.)

- Identify one or two new things you’ll do together as a family to improve the ways you give feedback to each other in the coming week. Make a note on the calendar for a week from now, and then use the tip sheet to give yourselves feedback about your feedback!

Variation

If you enjoy watching contest reality shows (e.g., singing, cooking, fitness.) together, watch the kinds of feedback people give to the contestants. Then discuss:

- What can you learn from what they say and do?

- What motivated contestants? What set them back?

- Which strategies did they use or not use?

- What would work in your family (recognizing that the high-visibility context of a TV show makes some things work there that won’t work at home)?

Advocate: Stand up for me when I need it (three family activities)

One of the powerful ways parents provide support is by advocating for kids, or speaking up for them when they need it. Sometimes we need to advocate for each other just because things aren’t working well, there has been a misunderstanding, or other everyday challenges arise. But sometimes there are bigger issues at stake, such as when children are mistreated, singled out, bullied, or overlooked due to:

- Race, ethnic, or cultural background;

- Gender;

- Home language;

- Mental or physical health needs;

- Sexual orientation or gender identity;

- Religious or cultural practices, dress, or beliefs;

- Neighborhood or family income; or

- Other personal and family situations and characteristics.

In some cases, just speaking up can make a difference and correct a situation. In other cases, though, you may encounter discrimination or prejudice, and advocacy can become vital, intense, and all-consuming. Advocating for a family member can be hard work, and it may be unfamiliar territory for many families. To help you get started, check out these 10 Tips for Advocating for Your Child. These activities encourage your family to talk openly about the ways you need to advocate for each other and others—including when to step in and when to hold back. They also highlight the need to connect with others who are dealing with similar challenges. These people can also provide support and encouragement to your family.

1. I Have Your Back 25 min

Sort through the times and ways you need to stick up for each other about big and little stuff.

What are the big and little ways you stick up for each other in your family because you care for each other and want to support each other? When have you felt like others may have let you down? This activity gives your family a chance to think about the ways you already advocate for each other—and where people might need more support.

- Introduce the topic of advocating for each other as part of the way family members support each other. Give each family member a pen and several small sheets of paper (paper scraps, note cards, or sticky notes such as Post-it notes).

- Talk about the description of advocacy noted above. Agree on what advocacy means for your family.

- On each different sheet of paper or card, have family members work separately and write down the places where either they advocate for other family members or other family members advocate for them. (There should be one idea on each sheet or card.)

- When people run out of ideas, share all the ideas. Sort them out so that all the similar ideas are grouped together.

If no one came up with any ideas of where they needed advocacy support for their issues, think together about whether there are other people they know who need advocacy support that could be provided. Continue the activity, but focus on how your family might advocate on behalf of these people.

- Then ask if there are any other places where family members spend time that they wish someone would advocate for them, but aren’t. Maybe there are times when they feel like others have let them down. Write them on additional cards or notes, if these examples come up.

- Keep each pile together, then sort them on a table based on how much advocacy is needed in each place. So, for example, the place that requires the most advocacy effort would be on the right and the place that requires the least advocacy effort would be on the left.

- Talk about the kinds of advocacy support that family members need on both ends of the continuum—from a lot of advocacy (on the right side of the table) to not much advocacy (on the left side of the table). Discuss these kinds of questions:

- What does a lot of advocacy mean for your family in these situations?

- What’s involved, and what needs to happen?

- What results have you seen so far? What would you like to see?

- After you’ve talked about the various kinds of advocacy support you need from each other, talk about how your family wants to work together so that everyone has the opportunities and supports they need. Pick one or two things you will try to do for the first time for each other in the next week.

2. Step in or Hold Back 30 min

Examine when you need to get involved and when it’s better to let people work it out on their own.

Are there times when what we think is being an advocate for each other crosses the line to being intrusive or overprotective? How do we know when to let someone take on a challenge alone? There are no simple answers to those questions. This activity helps your family set some ground rules for when to step in and when to hold back.

- Bring everyone together. Tell stories about times when people in your family have advocated for each other in small or large ways as a way of supporting each other. (Sometimes we talk about people who “go to bat” for us or “go out on a limb” for us or “have our backs.”) Adults might remember stories from when they were growing up. As you tell stories to each other, use these and other questions to fill in details:

- What happened?

- Why did they do it?

- How did they do it?

- How did other people respond?

- How did it feel to you? (There may be both positive and negative feelings.)

- What, if anything, changed after that?

- If all the stories you tell seemed positive, add some stories about times people said they were advocating for you, but they were really intrusive and or taking over for you. You might remember being embarrassed or angry.

- There may be other instances when you really needed someone to advocate for you, and they wouldn’t do it. What happened then?

- Give time for everyone to tell at least one story. Then talk about why you think people might get over-involved. Are they afraid that bad things will happen if they don’t? Do they not trust other people? Do they need more control? Are they overcompensating for not being involved in the past?

- Then talk about what was different between the positive and negative memories. What did the people who seemed really helpful do that was different?

- Based on your experiences and stories, brainstorm (and write down) your family’s own guidelines for how you’ll draw the line between being a strong, helpful advocate instead of meddling in unhelpful ways. Some things to consider:

- Do both people believe that having someone step in is the best approach?

- What would be the most effective approach to achieving the goal you have?

- Is the issue or challenge something the person involved has the skills to negotiate, even if it’s a bit scary or challenging?

- What are the consequences if it doesn’t work out? Are they severe enough to justify someone else stepping in?

- How could you use this experience to develop new skills and confidence for family members to be self-advocates?

- What kind of advocacy role is needed? Does the advocate really need to lead the effort (“Do all the talking”), or is it better for them to be with the person as a supporter, but to let them take the lead?

- Decide together how you’ll help each other live by the guidelines you set. The next time something comes up, check whether the guidelines you set are helpful, or if you need to refine them to make them more useful.

3. Support from Allies 30 min (plus some individual research time)

Connect with supporters and allies as you advocate for each other—and for changes in society.

The challenges you face that require advocacy are likely challenges that other families also face. Use this activity to create an informal directory of other families or organizations that might be allies for your family on particular issues—whether you’re looking for people to support you through a difficult situation or you want to band together with others to advocate for changes in public attitudes or public policies.

- Bring your family together to think about any issues or challenges you’re facing as a family (or someone in the family is facing) where you might value having some allies or advocates from beyond your family. Examples might be:

- Your family is going through a transition, such as moving to a new school or going through divorce;

- You have increased concern about a public issue, such as crime in the neighborhood;

- A child has identified (come out) as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or gender nonconforming;

- A child is struggling in school, and you don’t feel like the issue is being addressed adequately;

- A family member has a chronic medical condition or mental health issue; or

- A child is facing bullying or discrimination in school or another setting.

- Identify one or two of these situations where having other people you could turn to for help, encouragement, or advocacy for your family or the issue would be useful to you.

- Assign each family member (based on their skills and interests) one place they will look for resources or connections you could use. These may include:

- Trustworthy friends and extended family who you know would be there for you. If you’re comfortable, talk with them about the situation and see who they know who might have expertise, interests, or networks they could tap for you.

- Professionals (doctors, counselors, teachers, religious leaders) in your community who you know and trust. Ask them for recommendation or referrals.

- Check the Internet for reputable local and national organizations. (Look them over carefully to determine if their information is reputable.)

- Visit your local library to find directories of national or local resources. A librarian will often know about reputable organizations or how to find them.

- Give a few days for people to do their research. You don’t need to follow up on it all at this point; just gather it so you can decide together what’s most useful.

- After everyone has completed their research, come together to see what you’ve found. Talk about what you’ve learned, and ask yourselves questions about these resources to see if they’re a good match with your issue, priorities, and values.

- Decide if there are two or three options you want to get more information from, connect with, or to try out. Make a plan for getting started. In some cases, this may be as simple as arranging to meet someone for a conversation.

- Keep your list of resources so you can expand your advocacy network if and when you need it.

Set boundaries: Put in place limits that keep me on track (two family activities)

Part of growing up is being accountable to clear and consistent limits, boundaries, or rules. Of course, the specific limits may vary depending on:

- The family’s circumstances, neighborhood, or environment.

- The family’s beliefs, values, and priorities.

- The age, maturity, and other personal qualities of the child.

It’s easiest to think about limits and rules as boundaries that adults set to guide young people’s behaviors. Setting those boundaries is an important of adult responsibility. In addition, we all rely on limits to keep us on track, heading in the right direction.

Through these activities, your family thinks together about the ways family boundaries help—and when and whether they might be adjusted.

1. Playing without the Rules 40 min

A game with inconsistent rules shows the value of limits in our lives.

Sometimes it sounds fun to live in a world with no rules or boundaries. But what might it really be like? This family activity gives you a chance to experience playing with no rules as a springboard for talking about what makes rules and limits valuable and work well.

- Pick a board game, card game, or outdoor game that everyone in your family enjoys. (Electronic games don’t work for this activity.)

- Start playing together, using all the normal rules.

- After you’ve played a few minutes or a couple of rounds, let the person whose birthday is nearest to today pick one game rule you will eliminate. Play for a bit without that rule.

- Then have someone else pick a second rule to eliminate. Play without those two rules. Continue until everyone has picked a rule to eliminate—or at least for as long as you can before the game breaks down in chaos.

- Bring everyone together to talk about your experience. Use these prompt questions:

- What was your first reaction when you learned we were going to eliminate rules? How did your mood shift as rules were eliminated? How did you react?

- What was it like to be the one to eliminate a rule? What was it like to be someone who had to play without a rule that someone else eliminated?

- How did eliminating the rules affect your ability to play the game well?

- Think about other areas of life. How are these aspects of life similar to this game in terms of what happens when rules are eliminated? How are they different?

- What does this tell us about the value of rules and limits in our lives and in our families? What makes rules work well? When don’t they work well? (Some things others see as valuable include limits being consistent, fair, reasonable, and set collaboratively so that everyone has a say.)

- Conclude by thinking together about what kinds of rules, limits, or structure make life go more smoothly. Think about how you help each other learn and grow by the ways you set limits for each other.

2. Adjusting as We Grow 20 min

Talk about the different limits you have in your family at different ages.

Effective rules create a structure, set clear expectations, and help family members stay safe and make good choices. This activity prompts your family to think about how boundaries have changed as the family has grown up and as kids have matured.

- Tape together several sheets of paper to create a long, skinny “banner” you can add a timeline to. Draw a line down the center, and put a label for each age of children, from birth to age 20 (or older, if you prefer).

- Give each child in the family a different color of marker (with adults borrowing a child’s marker, when needed).

- Write down different years when you remember setting and adjusting rules as kids each have grown up. For example, some families say “no TV until age 2” or “all homework done before hanging out with friends.” These rules may have shifted as kids have grown up, and there may be places where the rules were slightly different for some kids than others. Just jot down what you remember.

If you’re having trouble, you might think of rules or limits you have or had in the following areas:

- Education (current and future)

- Health, fitness, and nutrition

- Technology/screen use (TV, cell phones, video games)

- Time spent practicing, studying

- Schedule (wake-up times, bedtimes, mealtimes)

- Alcohol or tobacco use

- Music choices (or volume)

- Time with friends

- Safety

- Time spent alone (unsupervised)

- After you’ve filled the timeline, talk about these questions together as a family:

- What patterns do you see? Did anything surprise you as you created your list?

- Have there been ages when a lot of limits have shifted at the same time? What prompted those shifts? Do you see some more shifts being needed soon?

- How do you know when it’s time to re-evaluate a rule or limit?

- What have you done to make sure that your family’s limits are clear, fair, and consistent? Are there areas where this has been hard? What might help?

- If you were to change one thing about the current rules or limits in your family, what would you change? How would you go about that together?

If you can’t agree to rules or limits, try activities in the Share Power section, particularly the ones on negotiation.

Learn About It

What Does It Mean to Provide Support?

![]() Children need their parents’ support in many practical ways. Providing this support helps young people stay on track to learn, grow, complete tasks, and achieve goals. It involves four actions:

Children need their parents’ support in many practical ways. Providing this support helps young people stay on track to learn, grow, complete tasks, and achieve goals. It involves four actions:

- Navigate: Guide me through hard situations and systems.

- Empower: Build each other’s confidence to take charge of life.

- Advocate: Stand up for each other when we need it.

- Set boundaries: Put in place limits that keep each other on track.

When we say support, we often mean different things. Many of the actions related to expressing care can also be considered support. Emotional support is part of express care in Search Institute’s research. For us, providing support focuses on the practical things we do for each other.

How Do Families Provide Support?

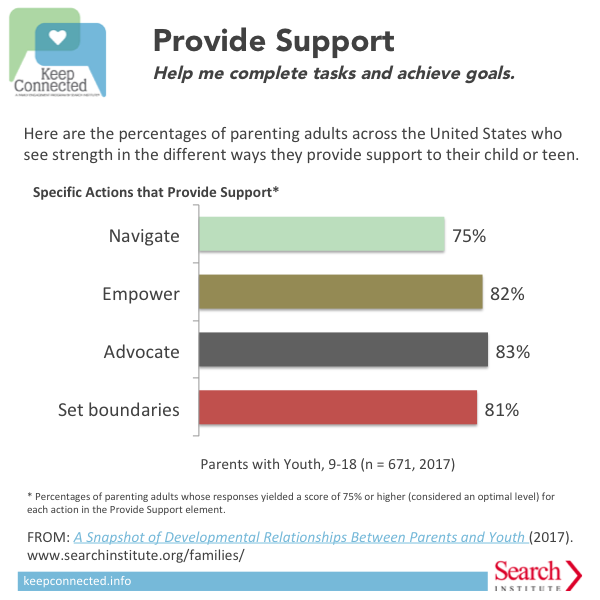

About eight out of ten U.S. parents are strong in how they provide support for their children, according to Search Institute surveys. For more research on providing support in family relationships, check out Search Institute’s research on families.

- Take the Provide Support quiz to explore the ways you provide support in your family.

Why Does Providing Support Matter?

Everyday support in the family

We all need support to learn, grow, and reach goals. Research shows that support from parents plays a big role in how well children do, including:

- Higher GPA and better adjustment in school;

- Higher self-esteem and lower depression;

- Lower rates of substance abuse; and

- Less stress or fewer emotional problems.1

Support for parenting adults

Parents do better when they have support at home and from extended family and friends. For example:

- Work-family conflicts are less stressful when they have a lot of support at home, including from their partner.2

- When parents have more support from others, they’re more likely to use positive parenting practices.3

- Parents who have strong support (especially in violent neighborhoods) are less likely to mistreat their children.4

Too much support?

As important as support is, you can also overdo it. If parents do things for their kids that take away their growth, autonomy, and learning (or don’t do enough to challenge growth), it hurts kids’ development.10

Support in the face of challenges

Some situations call for extra support. These situations include school struggles, medical issues, and big life transitions. Here are some examples:

- Teenagers who face bullying in schools are more likely to do well in school if they have a lot of support from their families and peers.5

- The stress of living in a dangerous neighborhood is reduced when young people have a lot of support from parents.6

- Children who use special education services depend on their parents to speak up for their needs and strengths.7

High levels of parental (and other) support is associated with lower levels of depression and a higher quality of life among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth.8,9

Read It

Provide Support

An important way families stick together is helping each other in practical ways to stay on track to learn, grow, complete tasks, and achieve goals.

|

Jingle Dancer (Family Strength: Encourage) Written by Cynthia Leitich Smith Illustrated by Cornelius Van Wright and Ying-Hwa HuGet the Book For your school or organization. For your family, or visit your local library |

|

My Name is Yoon (Family Strength: Encourage) Written by Helen Recorvits Illustrated by Gabi SwiatkowskaGet the Book For your school or organization. For your family, or visit your local library. |

|

Salt in His Shoes: Michael Jordan in Pursuit of a Dream (Family Strength: Guide) Written by Deloris Jordan and Roslyn M. Jordan Illustrated by Kadir NelsonGet the Book For your school or organization. For your family, or visit your local library. |

Research Sources

Try It

- Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2012). Delivering effective performance feedback: The strengths-based approach. Business Horizons. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.10.004

- Archer, J. C. (2010). State of the science in health professional education: Effective feedback. Medical Education. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x

- Thurlings, M., Vermeulen, M., Bastiaens, T., & Stijnen, S. (2013). Understanding feedback: A learning theory perspective. Educational Research Review. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2012.11.004

Learn About It

- Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 47–61. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6

- Van Daalen, G., Willemsen, T. M., & Sanders, K. (2006). Reducing work-family conflict through different sources of social support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 462–476. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2006.07.005

- Lee, C.-Y. S., Anderson, J. R., Horowitz, J. L., & August, G. J. (2009). Family income and parenting: The role of parental depression and social support. Family Relations, 58, 417–430. doi:10.2307/40405700

- Martin, A., Gardner, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2012). The mediated and moderated effects of family support on child maltreatment. Journal of Family Issues, 33(7), 920–941. doi:10.1177/0192513X11431683

- Rothon, C., Head, J., Klineberg, E., & Stansfeld, S. (2011). Can social support protect bullied adolescents from adverse outcomes? A prospective study on the effects of bullying on the educational achievement and mental health of adolescents at secondary schools in East London. Journal of Adolescence, 34(3), 579–588. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.02.007

- Bowen, G. L., & Chapman, M. V. (1996). Poverty, neighborhood danger, social support, and the individual adaptation among at-risk youth in urban areas. Journal of Family Issues, 17(5), 641–666. doi:10.1177/019251396017005004

- Trainor, A. A. (2010). Diverse approaches to parent advocacy during special education home-school interactions. Remedial and Special Education, 31(1), 34–47. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0741932508324401

- Simons, L., Schrager, S. M., Clark, L. F., Belzer, M. Olson, J., (2013). Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents, Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(6), 791‒793. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.019.

- Mustanski, B., & Liu, R. T. (2013). A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth, Archives of Sexual Behavior 42(3), 437–448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0013-9

- Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., & Tashner, T. (2013). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 548–557. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9716-3